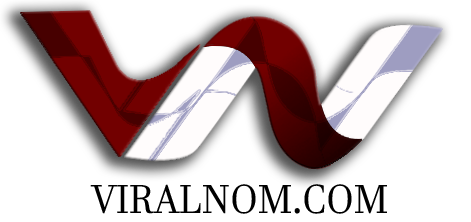

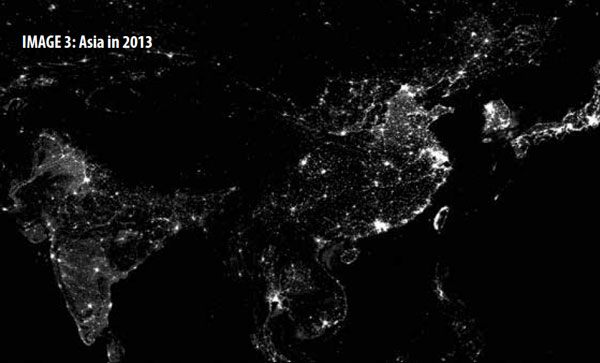

A large body of research shows that the brightness of a country’s nighttime lights. As seen from satellites, is highly correlated with GDP growth. The more money people have, the more likely they are to have lights on at night. Businesses will also stay open later, resulting in even more light.

Satellite images of night time lights have contributed to our understanding of economic activity for more than a decade. For example, nighttime lights can help approximate GDP growth in small spatial units over time. Recent technological innovations have expanded potential applications. Data is now available at a monthly frequency, in a finer spatial grid. And with more sensitive measurement of low-light areas. These innovations allow nighttime light data to be used to study the short-run impacts of economic events.

Early publications have demonstrated powerful applications of this new data to economics. Studies of natural disasters, lockdown measures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Domestic policy measures (such as demonetization in India). Trade shocks (such as tariff escalation between China and the United States) have all been undertaken using nighttime light data.

The relationship between night lights and economic development, however, is not always straightforward. In my study with Johns Hopkins University’s Yingyao Hu, we compare night lights with GDP, the official and most commonly used measure of an economy’s performance. We find that rich countries are indeed brighter than less developed countries, but there is no lack of exceptions.

Also Read: Artificial Intelligence Just Flew an F-16 fighter for 17 Hours

On a per capita basis, Nordic countries have almost always been the brightest spots on Earth. On the other hand, Japan, despite being a rich country, looks scarcely brighter than Syria did before the Arab Spring, most likely because of its energy conservation habits and high population density.

The study is part of the new field of “forensic economics.” Rather than just accepting government statistics at face value, researchers can use newly available streams of data, like those from satellite images, to double-check the data. For example, a 2013 study used prices from online retailers to argue that the Argentinian government was manipulating inflation statistics (pdf).

As more alternative data becomes available, it will be increasingly difficult for the manipulators of government statistics to get away with it.